Philippine Sea – Voyage Update #4

Philippine Sea Update #4

Guyot sounds like ‘Ghee-Yo’

We said goodbye to Minami-Daito without ever stepping foot on the island, but having explored some of the biodiversity living in and around its undersea limestone caves. Our ship, Kaimei, headed east toward a series of seamounts along the Kyushu/Palau ridge.

Though these seamounts were formed as an island arc, they are neither islands nor active volcanoes. The “not island” explanation is simple: because the seamount tops don’t break the ocean surface, they are not islands.

The “not actively volcanic” explanation requires a little tectonics fluency: about 25 to 28 million years ago, plate subduction created the seamounts of the Kyushu/Palau ridge. However, complex tectonic dynamics have ceased the volcanism of these seamounts turning them into “extinct volcanoes’.

Should you lament this loss, there are plenty more active seamounts and volcanoes being created and fuelled by the famed Ring of Fire. Some to many of the Kyushu/Palau seamounts aren’t “mounts” at all. Their pointed shape has been eroded, creating a flat, mesa-like structure called a table mount or guyot (pronounced ghee-yo). If you’ve read this far your rewards are: 1) clarity in understanding seamounts, and 2) the word “guyot” (!), a potential crossword answer, decent point-getter for Scrabble, or possible win for Wordle.

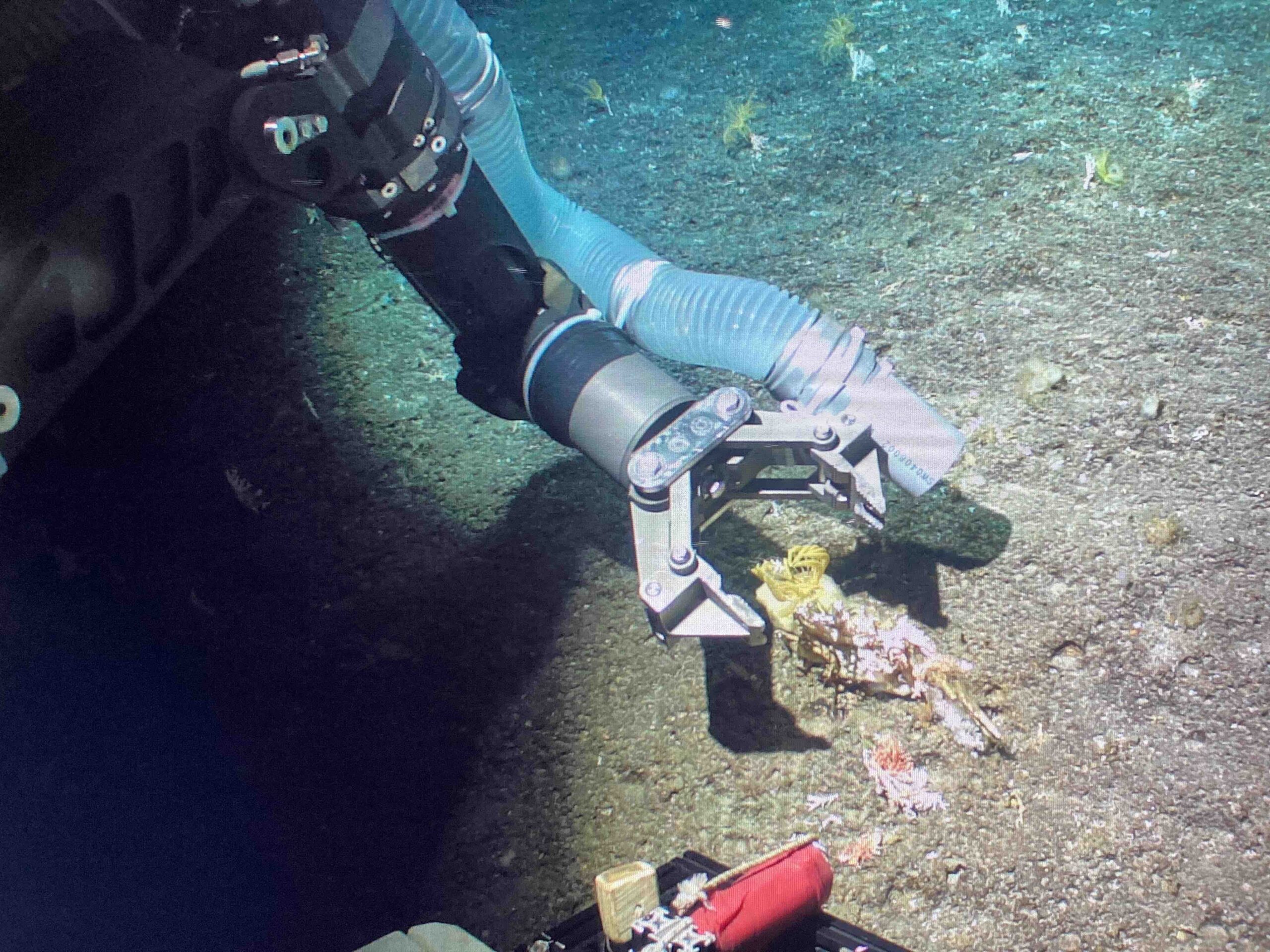

Pilots are a deep-sea scientist’s best friend

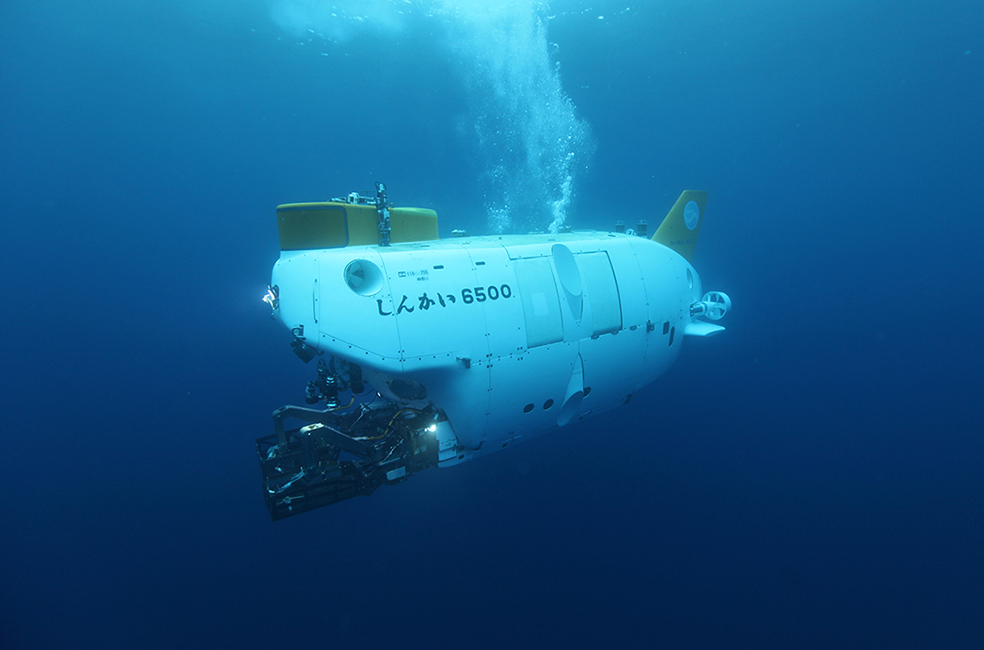

At whatever site we’ve explored, one of the ship’s two ROVs has been deployed. The ROVs of Kaimei are tethered to the ship and have moveable jointed arms, a suction tube, lights, boxes and canisters for specimen storage, thrusters for propulsion, and up to five cameras to record what is happening.

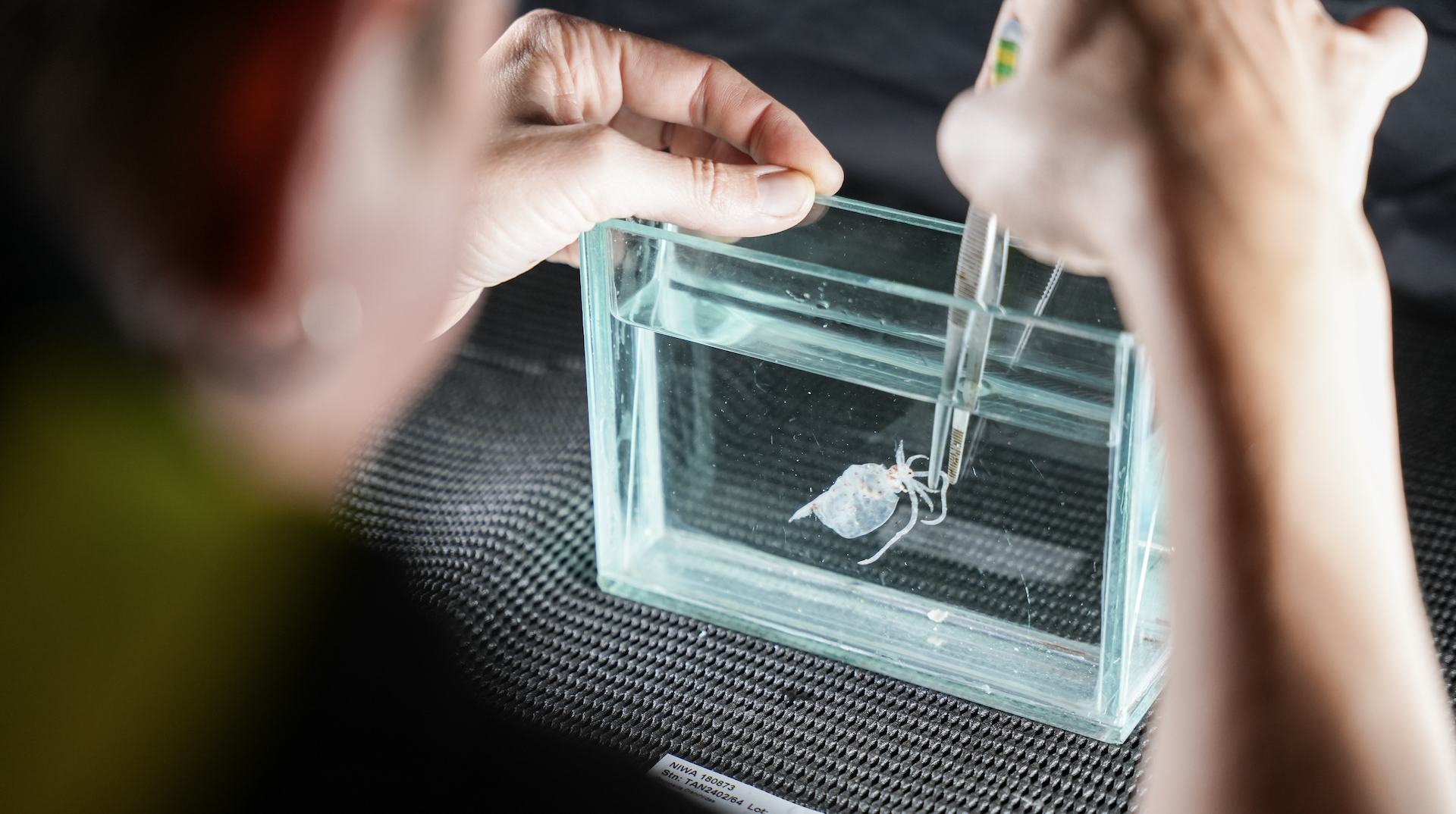

The pilots of these complex machines are onboard the ship in a specialized command room, but are in constant communication with scientists by radio. They focus the ROV’s camera(s) on known and mysterious creatures while the scientists debate their taxonomic identity and whether they should be collected. The pilots do this whilst simultaneously steering the ROV, negotiating ocean currents, and manipulating and deploying various analytical tools. The scientists gather near the bridge of the ship to watch a live feed of the ROV camera footage on several large monitors.

So far, Kaimei’s ROV pilots have navigated ocean caves without incident and deftly collected dozens of specimens from the seafloor and water column.

What the Philippine Sea and the Mojave Desert have in common

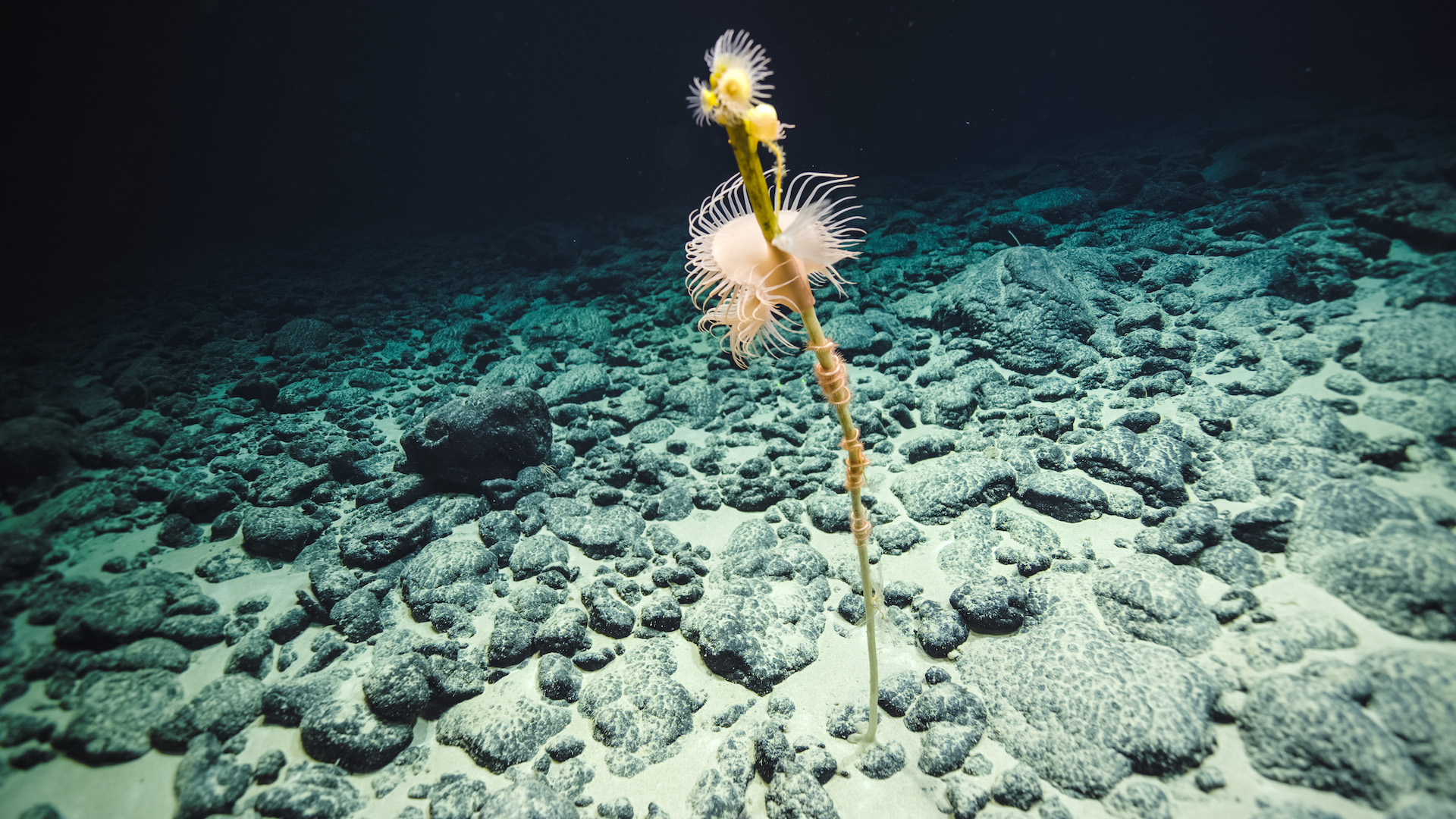

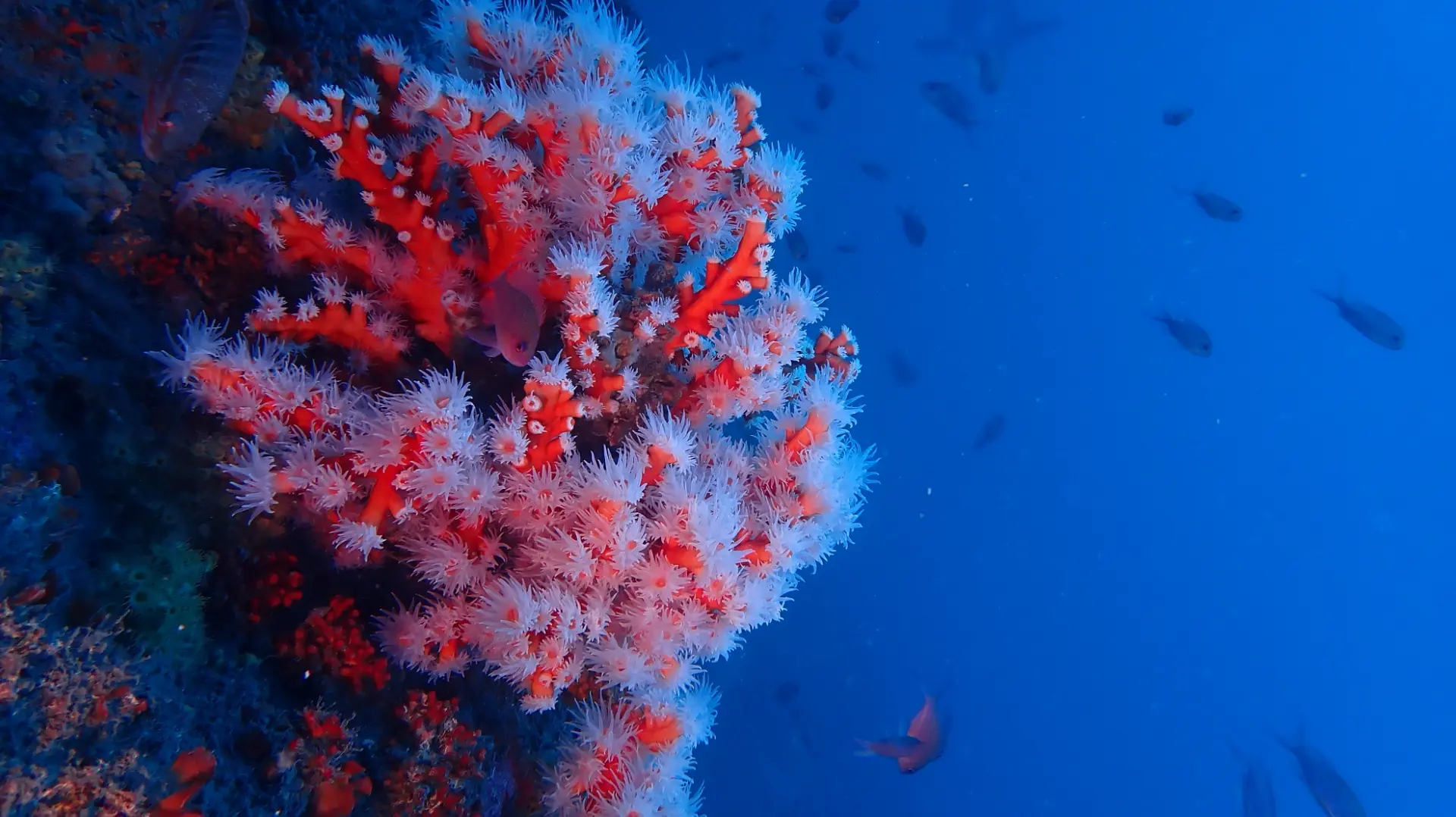

On the flat top of the seamount we’ve explored are expanses of sand and rock void of visible life, interrupted by oases of animals associated with an upright structure. At 300–400 meters deep, this relief is usually a soft or wiry protein-bodied coral. These are not the stony corals, colonial creators of shallow tropical reefs, but their evolutionary siblings – fleshy and flexible, whip-like, or branching.

At their base are hermit crabs, on their stalks are snails, swimming nearby are fish. Clinging to them are often one or more species of sea star or feather star (members of the weird and wonderful phylum Echinodermata), looking very plant-like as if they were flowers. Indeed, marine communities in which animals provide the structure that is usually created by plants in terrestrial environments have been called “marine animal forests”.

At upper bathyal depths (deep, but not that deep), there are no forests of animals or plants, but the mini oases of animals that do live there remind me of a plant-dominated environment of eastern Los Angeles County (and beyond) – the Mojave Desert. Both habitats share expanses of low biodiversity, punctuated with life.

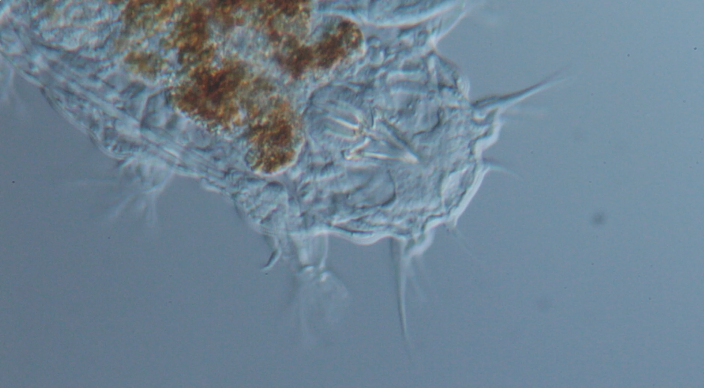

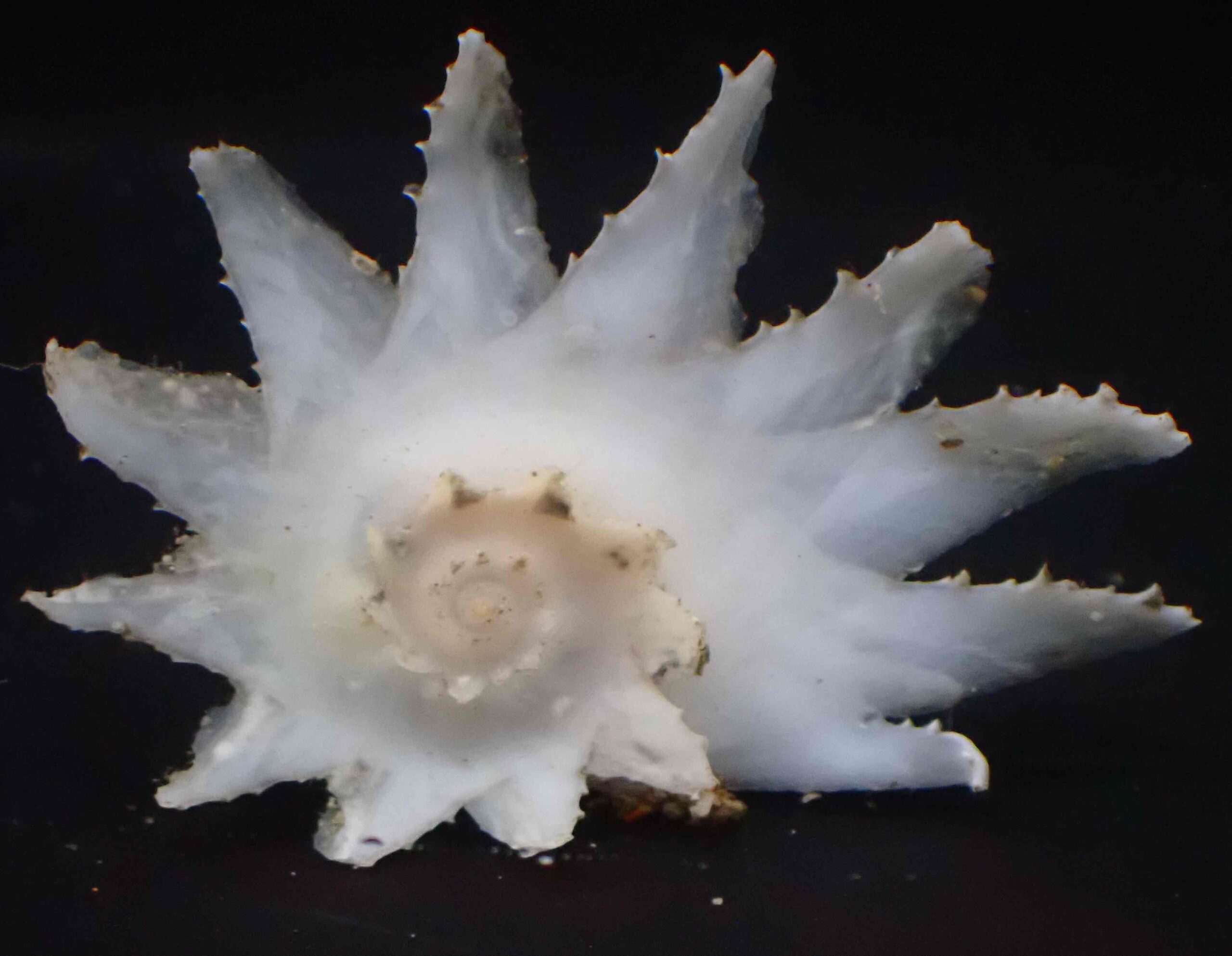

Collage of molluscs

It has been a banner week for molluscs. This being my first deep-sea research cruise, I’m not making that statement with the wisdom of experience.

However, I do know that it is one thing to see a shell in collections (as I typically do) and quite another to see it in its habitat.

Seashells are often appreciated for their colour, pattern, and shape, all of which are on display here. A reminder: Molluscs with shells make their shells,. and with few exceptions (for sea slug larvae), grow with them, and are attached to them for their whole lives.

Missed an update? Revisit Voyage update #1, Voyage Update#2, Voyage Update #3.

Thanks to Jann Vendetti for sharing this voyage update. This expedition is led by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), the Ocean Shot Research Grant, and NHK TV.

Featured Image Credits: Dimitris Poursanidis / Ocean Image Bank

Image credits: Google Earth, JAMSTEC

PHILIPPINE SEA

More about the voyage…

Ocean Census Philippine Sea is a Participant Expedition to explore the Kyushu-Palau Ridge and Minami-Daito Jima Island areas in the north western Pacific.

As part of the wider JAMSTEC Ocean Shot Expedition, led by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), the Ocean Shot Research Grant, and NHK TV, two participant scientists from the Ocean Census Science Network are joining the cruise onboard JAMSTEC research vessel KAIMEI.

Related News

Join the census

An Alliance of scientists, governments, marine research institutes, museums, philanthropy, technology, media and civil society partners.