Arctic Deep – Dive Site: The Knipovich Ridge

Arctic Deep Dive Site

Situated in the northernmost Norwegian-Greenland Sea, the Knipovich Ridge makes up part of the Arctic mid-ocean ridge system and offers an intriguing glimpse into the complex geological and biological history of the Arctic seabed.

The region is unique due to its well-defined rift valley, deep basins, and rugged topography, which provide a variety of habitats for marine life, including deep-sea corals, chemosynthetic ecosystems, and endemic species of benthic fauna.

Geological Background

The Knipovich Ridge is an ‘ultraslow-spreading ridge’ that extends approximately 550 kilometres from the Mohn’s Ridge to the Molloy Transform Fault. It’s oriented at an angle of 115 degrees to the Mohn’s Ridge and lies between 73°45’N and 78°35’N, with an average depth of 2,100 metres in the south and 3,000 to 3,500 metres in the north. The first full science operations dives conducted by The Arctic Deep expedition are taking place around 74°N at the underexplored lower reaches of the ridge network.

The Knipovich Ridge is part of the mid-ocean ridge system, a submerged mountain chain stretching 60,000 kilometres around the world like the seams on a tennis ball. The largest geological feature on earth, their existence was first hinted at by unexpected readings from 19th-century expeditions and transatlantic cable-laying efforts.

In the mid-20th century, sonar technology and seismic studies, especially the pioneering work of Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen, further illuminated the scale of these fascinating features. This research was initially dismissed by the wider scientific community but eventually led to the confirmation of the theory of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics.

Hailed by many as being as fundamental to the fields of geology and earth sciences as the discovery of DNA was to biology.

‘Ultraslow’ in the context of geological time should be put into perspective. The fastest spreading seafloor region is The East Pacific Rise, where the ridge segment that creates the Nazca and Pacific plates moves up to 142 mm each year. The Knipovich moves at around 15 – 17mm per year on average, which is less than half the speed fingernails grow.

Until the early 20th century, it was believed that there was insufficient volcanic activity associated with these ultraslow regions to support hydrothermal vent fields. In the early 2000s, a group of researchers detected the first hints of hydrothermal activity in the water column in the region.

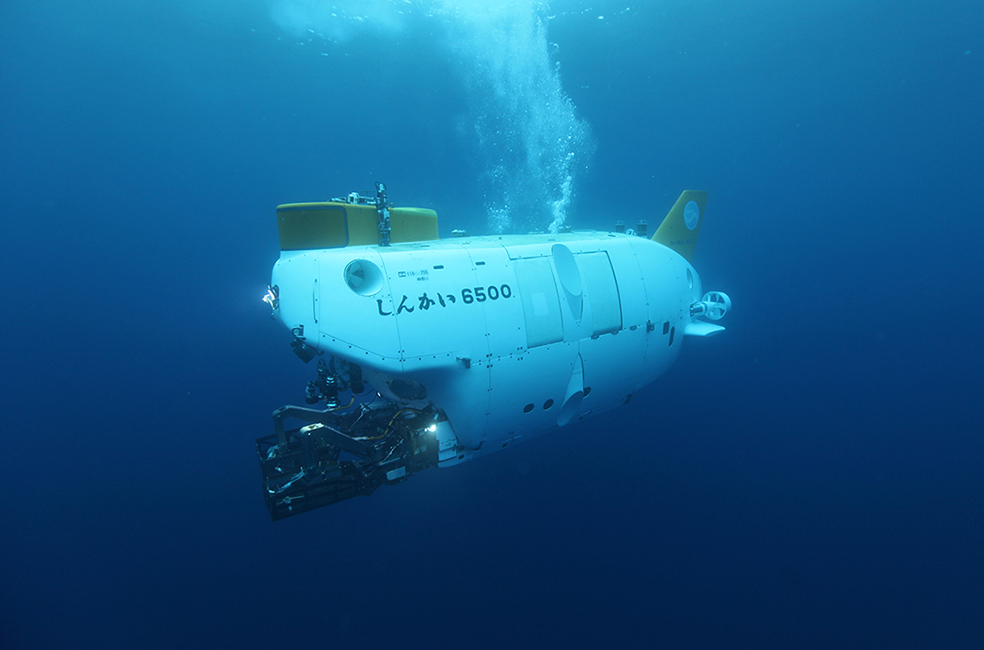

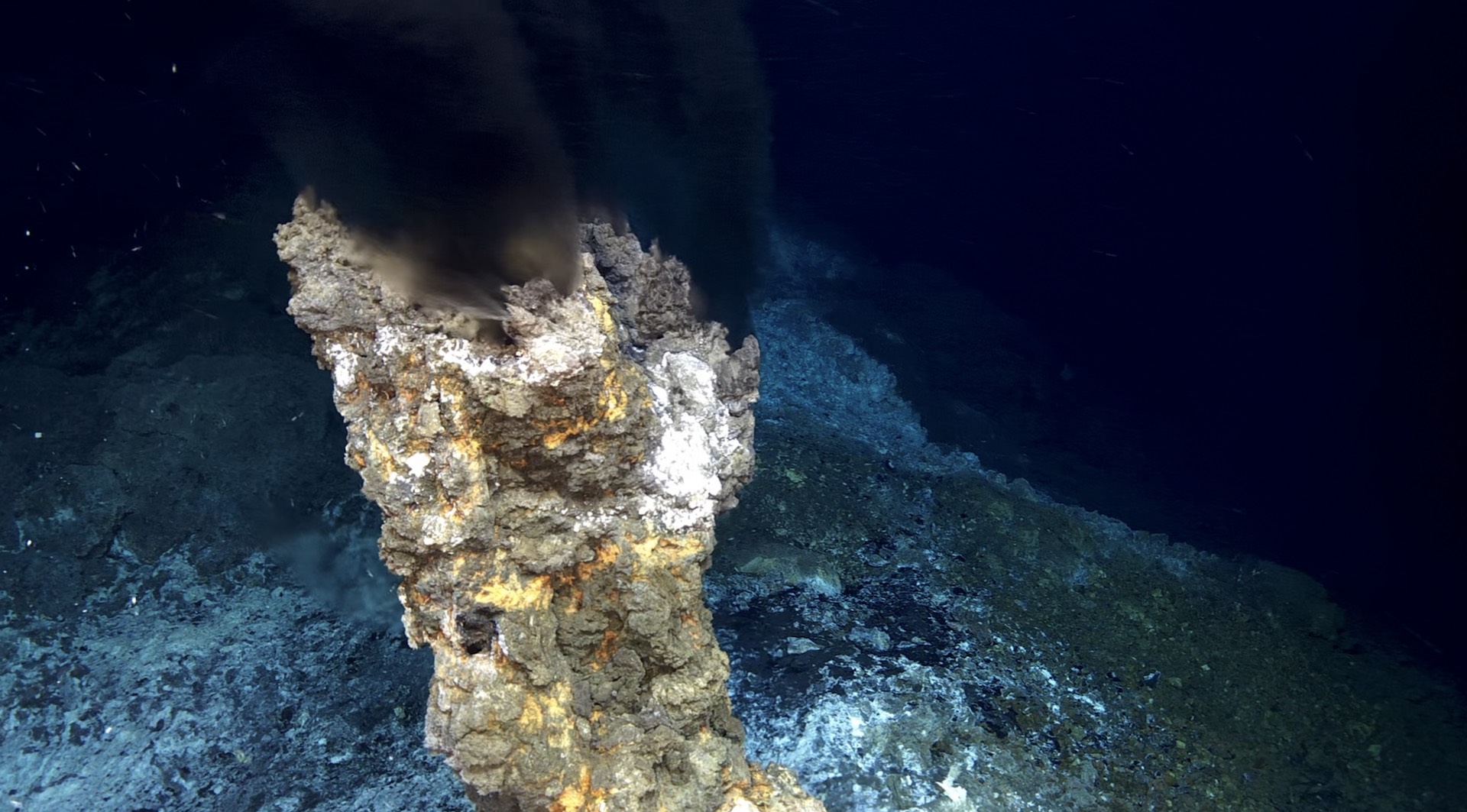

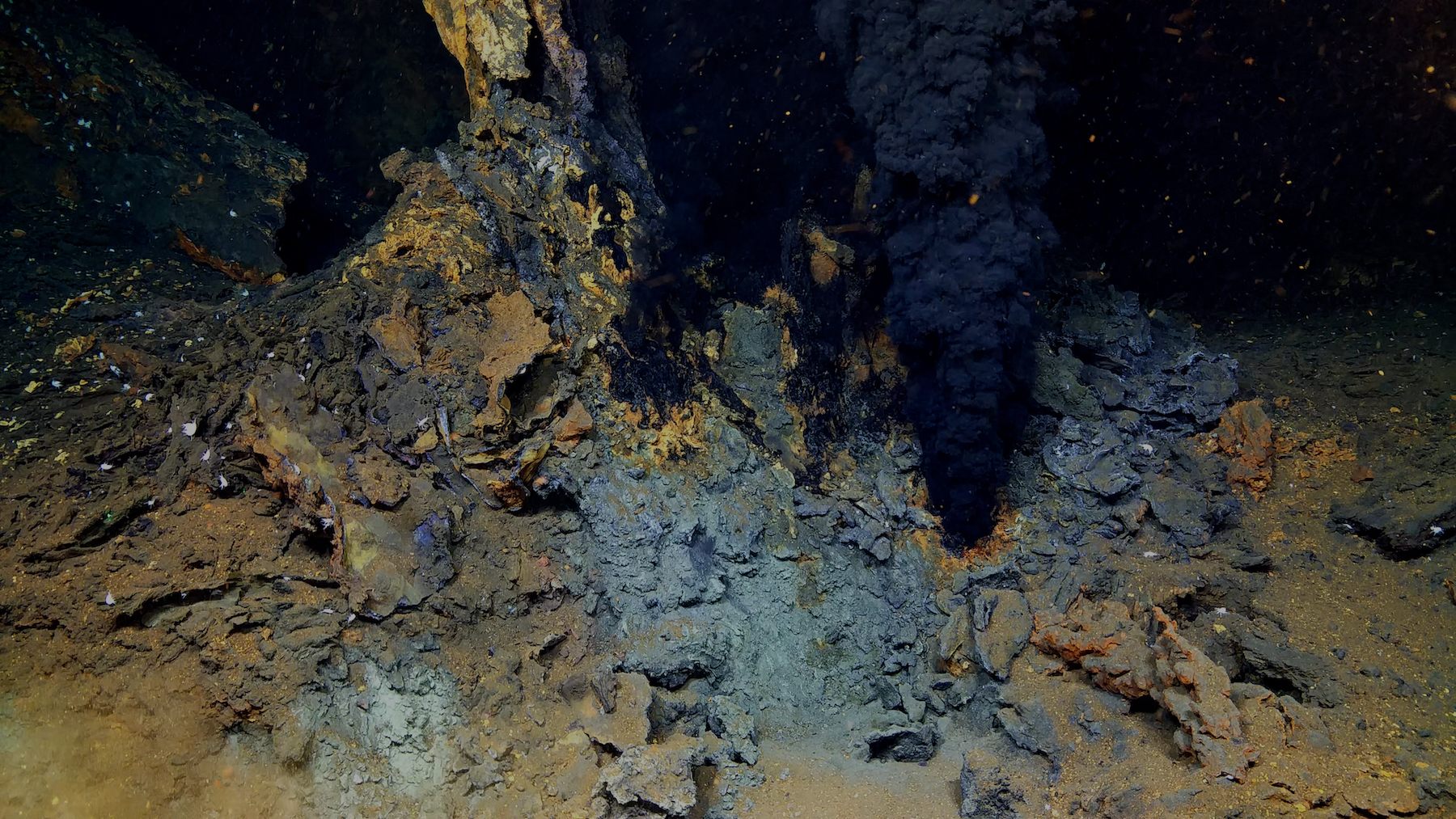

It was not until July 2022 that the Maria S. Merian MSM109 expedition explored the Knipovich and Molloy Ridges in search of hydrothermal vents. This expedition, led by MARUM, the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen and other institutions found evidence of hydrothermalism in two areas, including the Knipovich Ridge, where they discovered and named the Jøtul Hydrothermal Field, a 1 kilometre long and 200 m wide area with active and inactive vents. The Arctic Deep expedition will be visiting the Jøtul field sites as it makes its way further north. The southern areas where the initial Arctic Deep dives are focussed is still underexplored, and building on the work of earlier pioneering expeditions, the hope is that these first dives will discover more vent activity.

Biological Significance

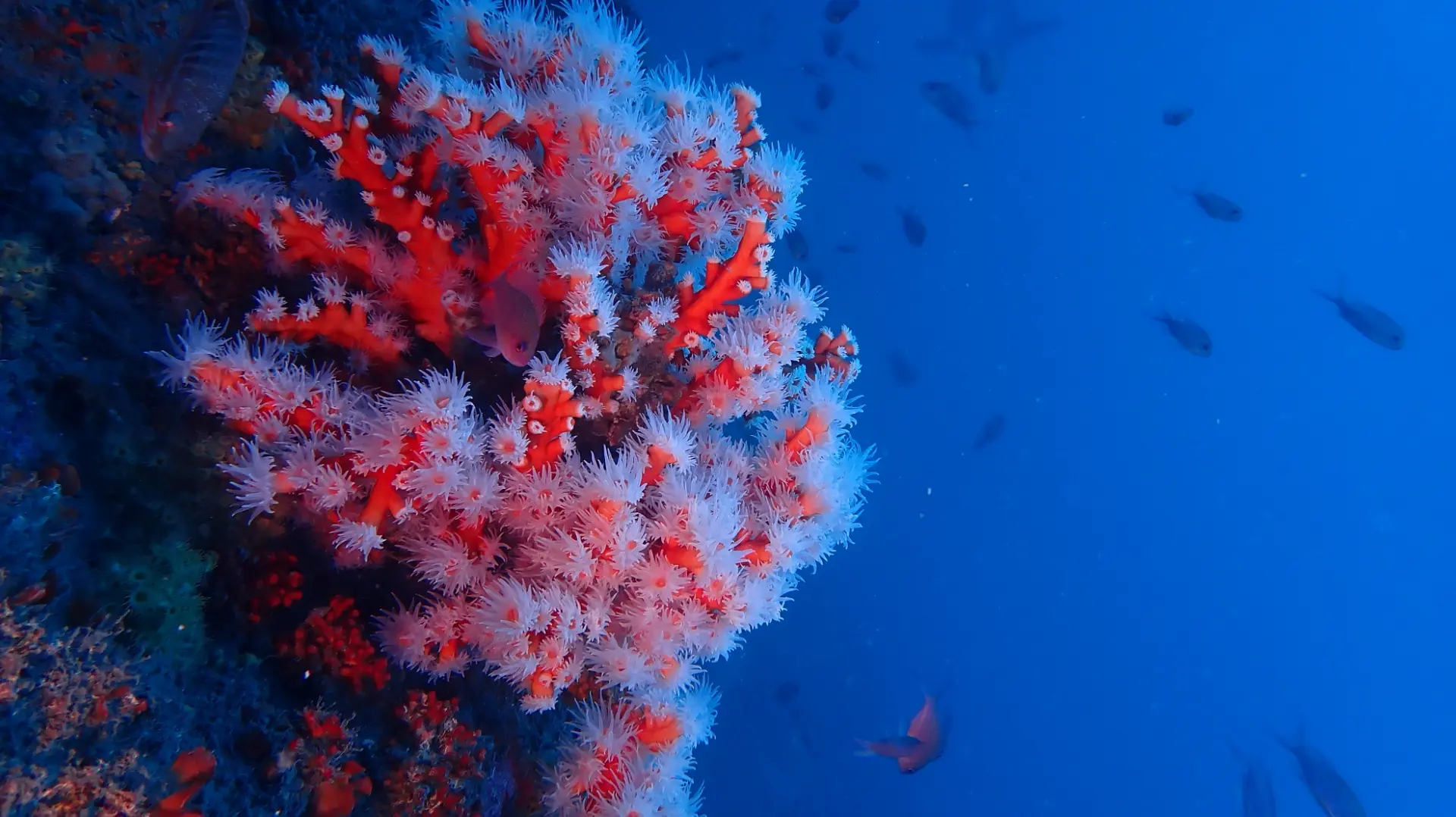

The Knipovich Ridge itself is ecologically important due to its varied habitats and unique marine life. The deep basins, rift valleys, and rugged topography create a range of ecological niches, contributing to the Arctic’s rich biodiversity.

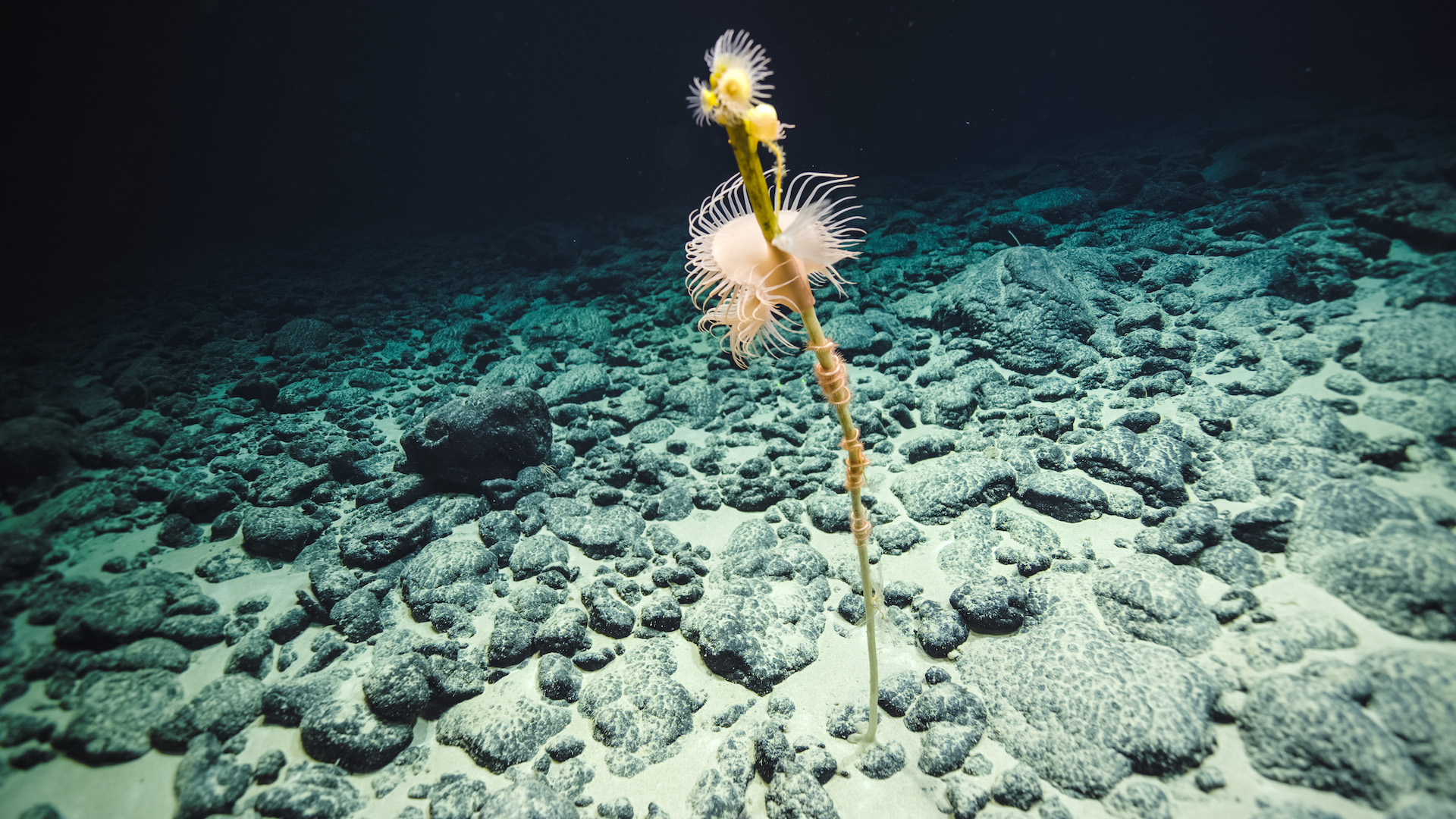

The region hosts a variety of hard and soft substrate communities, biogenic habitats formed by cold-water corals, as well as chemosynthetic ecosystems, including deep-sea hydrothermal vents and hydrocarbon seeps. These habitats are home to a fascinating variety of species. Deep-sea corals, such as Desmophyllum pertusum, create biogenic habitats, while chemosynthetic ecosystems host specialised species like siboglinid worms.

“Deep-sea hydrothermal vents are important because they are little islands of life. You find species around them that you won’t find anywhere else in the deep ocean, so it’s a great place to go looking for new species”

Professor Jon Copley of the University of Southampton.

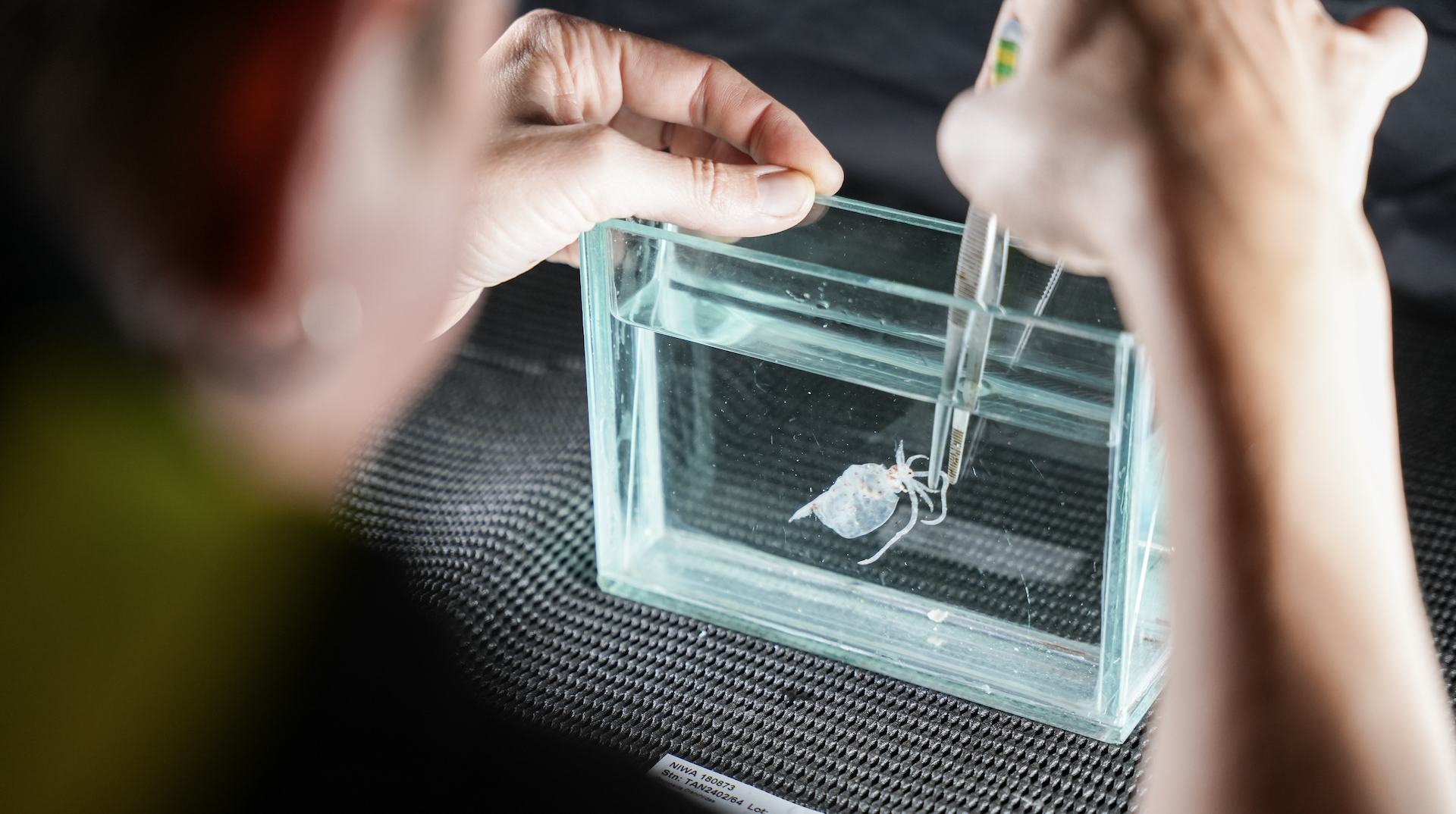

The biodiversity of the Loki’s Castle vent field is better understood thanks to the researchers from the University of Bergen (see below image also). Located near the Knipovich Ridge, it harbours unique Arctic vent fauna, including the tubeworm Sclerolinum contortum, unique amphipods, and small grazing gastropods.

The region also supports microbial life, including novel archaea like Lokiarchaeota, which highlight the diversity of life in these extreme environments. The Ocean Census team hope that they can locate similarly biodiverse habitats along the southern Knipovich Ridge, before turning their attention to the northern reaches and on to Molloy Deep.

References:

Find out more about the Ocean Census Arctic Deep Expedition.

Image Credits: Google Earth, Centre for Deep Sea Research (University of Bergen).

Related News

Join the census

An Alliance of scientists, governments, marine research institutes, museums, philanthropy, technology, media and civil society partners.