“The Perfect Pair” Symbiotic Relationships of the Deep Blue

Close ties through symbiosis

They say that two is better than one, and for some marine species, living as a pair means that they are able to survive, adapt, and thrive in complex and often challenging underwater environments.

Symbiosis refers to a close and long-term relationship between two different species, where at least one of the organisms benefits from the interaction.

In marine environments, symbiosis is especially common and plays a vital role in maintaining healthy ocean ecosystems. These relationships can take several forms, including mutualism, where both species benefit; commensalism, where one species benefits while the other is neither helped nor harmed; and parasitism, where one organism benefits at the expense of the other.

Below, we’re taking a look at symbiosis found in some of our discovered species, as well as what we’ve seen on expedition footage.

Feature Image Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

“We Go Together”

The dual benefits of mutualism

Snail & Anemone

During the Ocean Census x Schmidt Ocean Institute South Sandwich Islands expedition (2025) near Montagu Island, we observed a clear example of mutualistic symbiosis between an anemone and a snail.

The anemone attaches to the snail’s shell, allowing it to travel to new areas and gain increased access to food particles as the snail moves across the seafloor. In return, the snail benefits from protection and camouflage provided by the anemone’s stinging tentacles, which can deter predators.

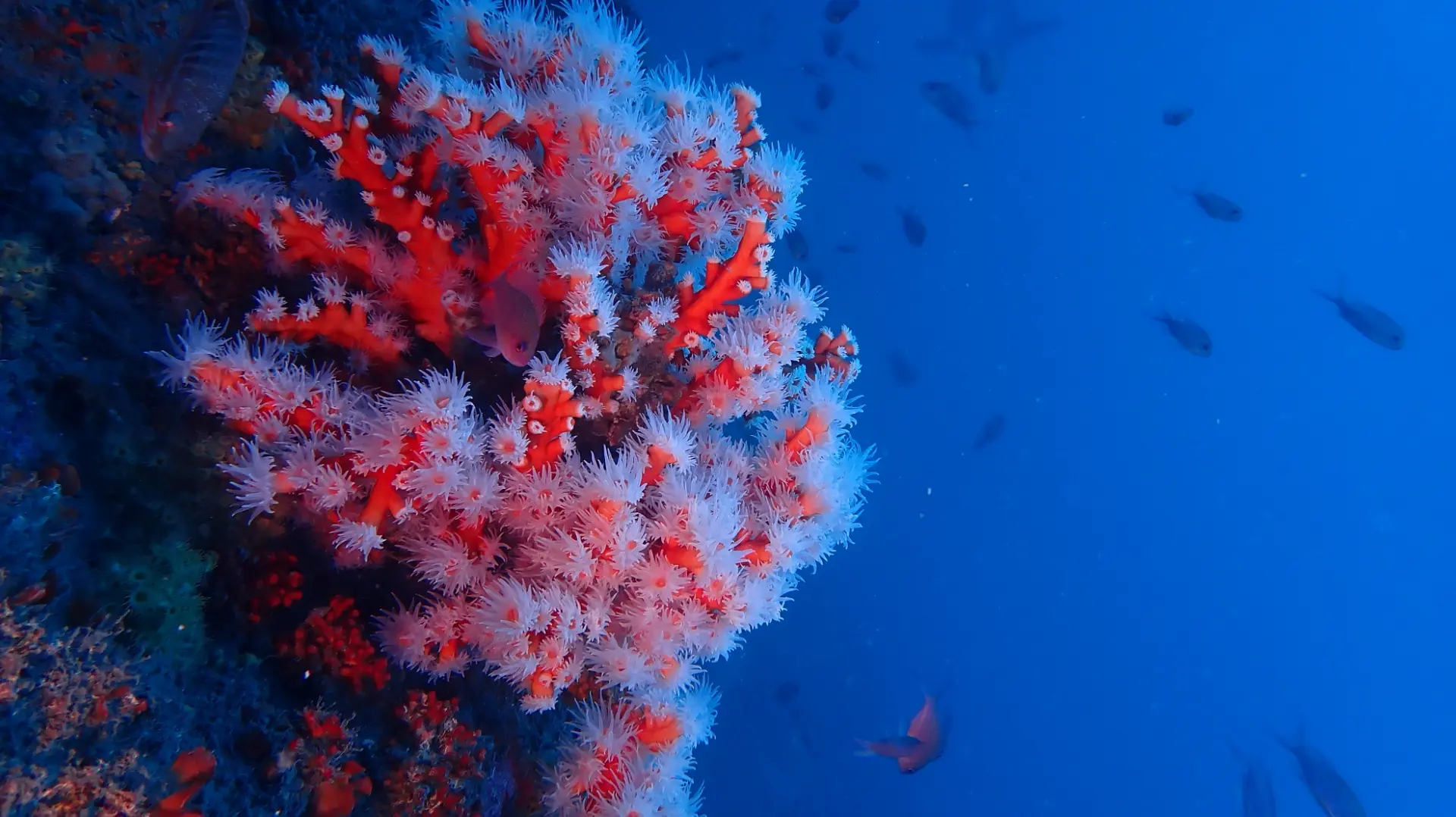

Polychaete and glass sponge

During the Ocean Census x JAMSTEC Shinkai (2025) expedition, we observed another example of symbiotic interaction involving polychaete worms and glass sponges in the deep sea.

In this relationship, the polychaete benefits by gaining a protected home within the sponge’s rigid silica skeleton, which provides a stable, three-dimensional structure rich in nutrients and shelter from deep-sea predators. In return, the glass sponge benefits from the presence of the worm, which helps clean its surface by removing accumulated debris and epibionts that could otherwise smother or damage the sponge.

“A helping hand”

Understanding the benefits

of commensalism

Barnacle & Cup-Coral

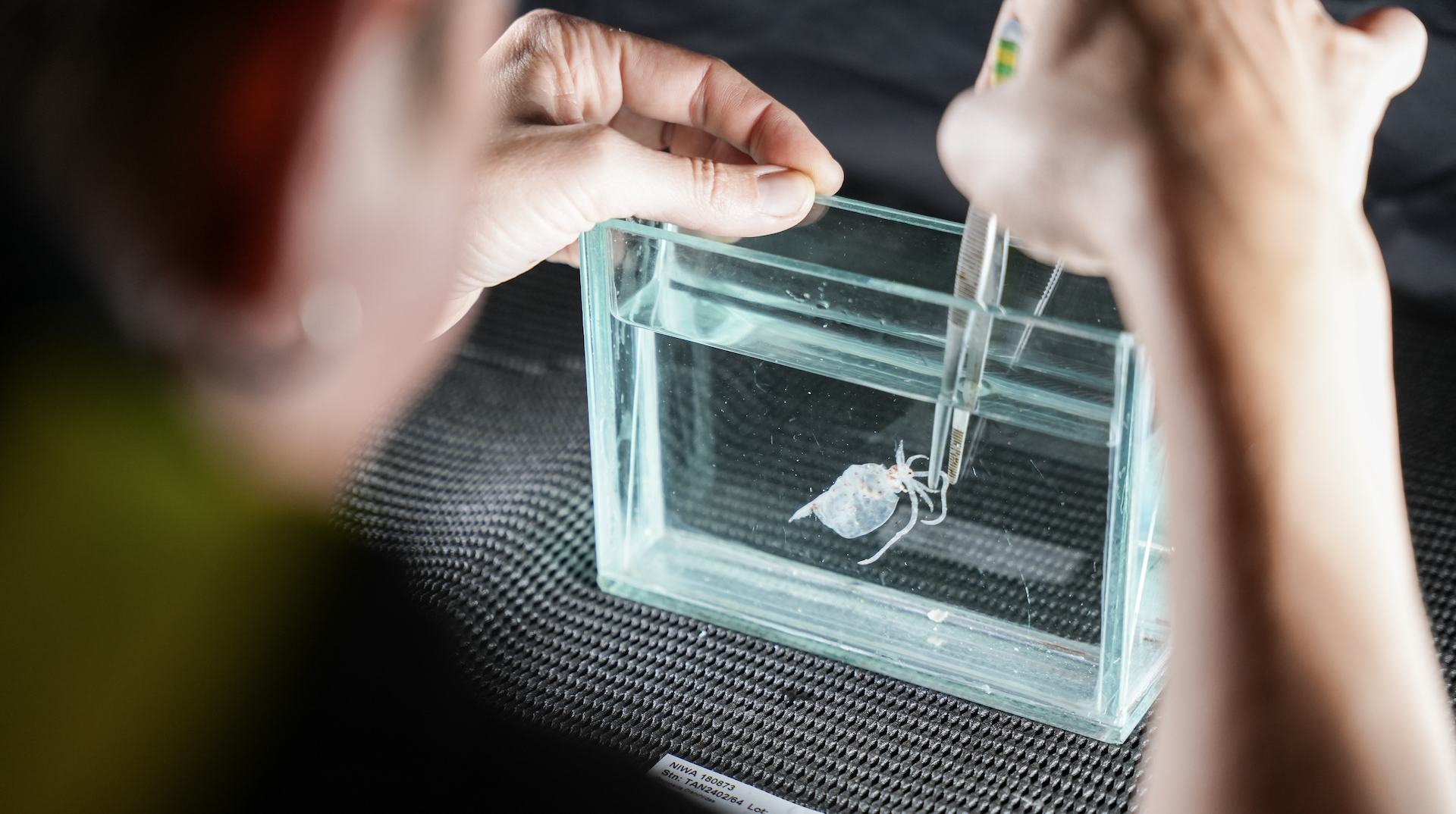

Andrew Hosie, one of our species discovery awardees, described a newly discovered stalked barnacle (Amigdoscalpellum calicicolum), at a depth of 900m off New Zealand, that appears to live in a commensal relationship with cup corals.

The species attaches specifically to the rim of the coral cup and is oriented toward the coral polyp’s mouth, suggesting a close ecological association. Larvae must navigate the coral’s stinging tentacles to settle on the living skeleton, after which the coral can grow around the barnacle without obvious harm, sometimes partially overgrowing it and leaving pits or grooves in the skeleton. While the coral host appears unaffected, the barnacle likely benefits from a stable attachment site and access to food.

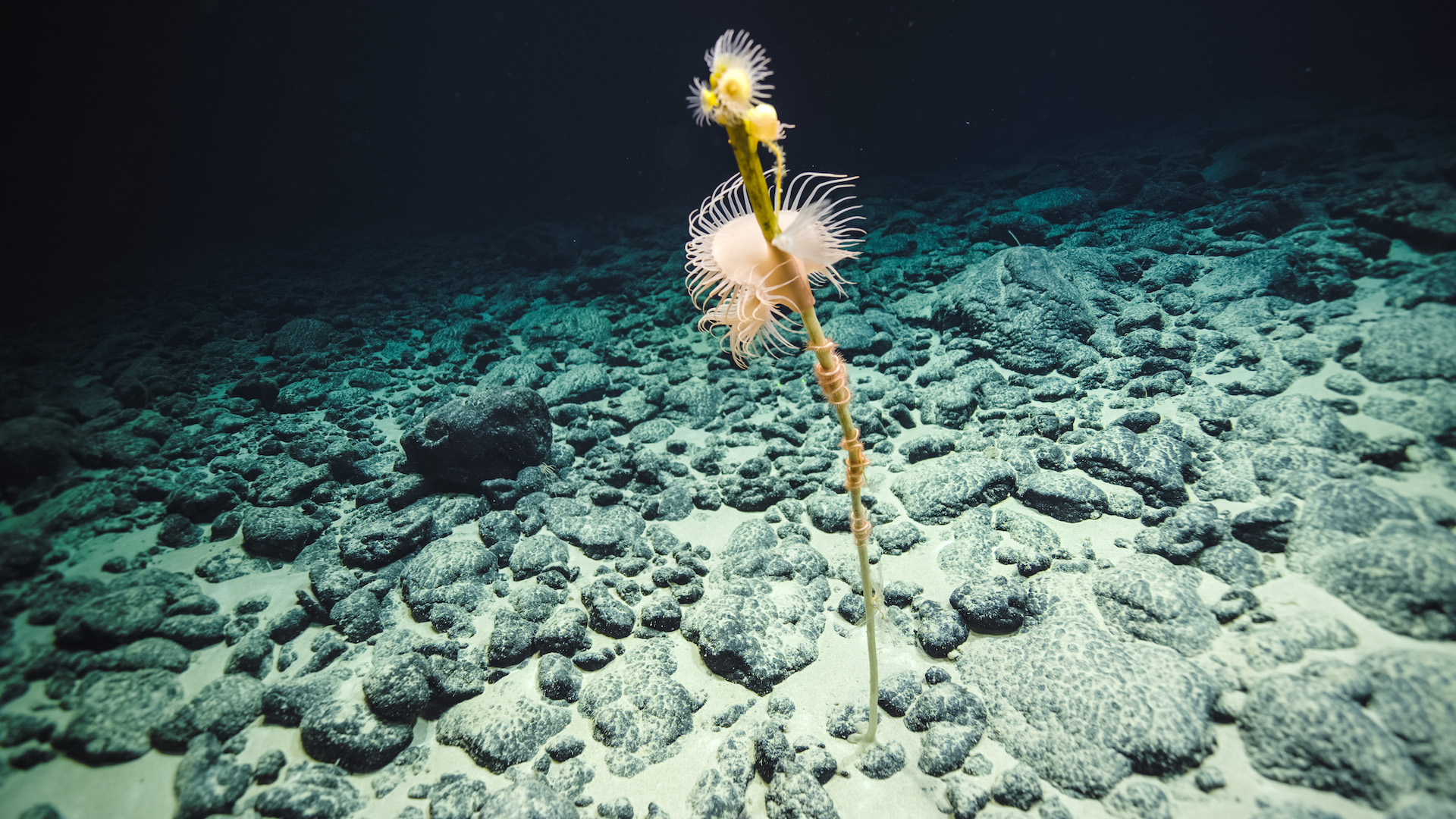

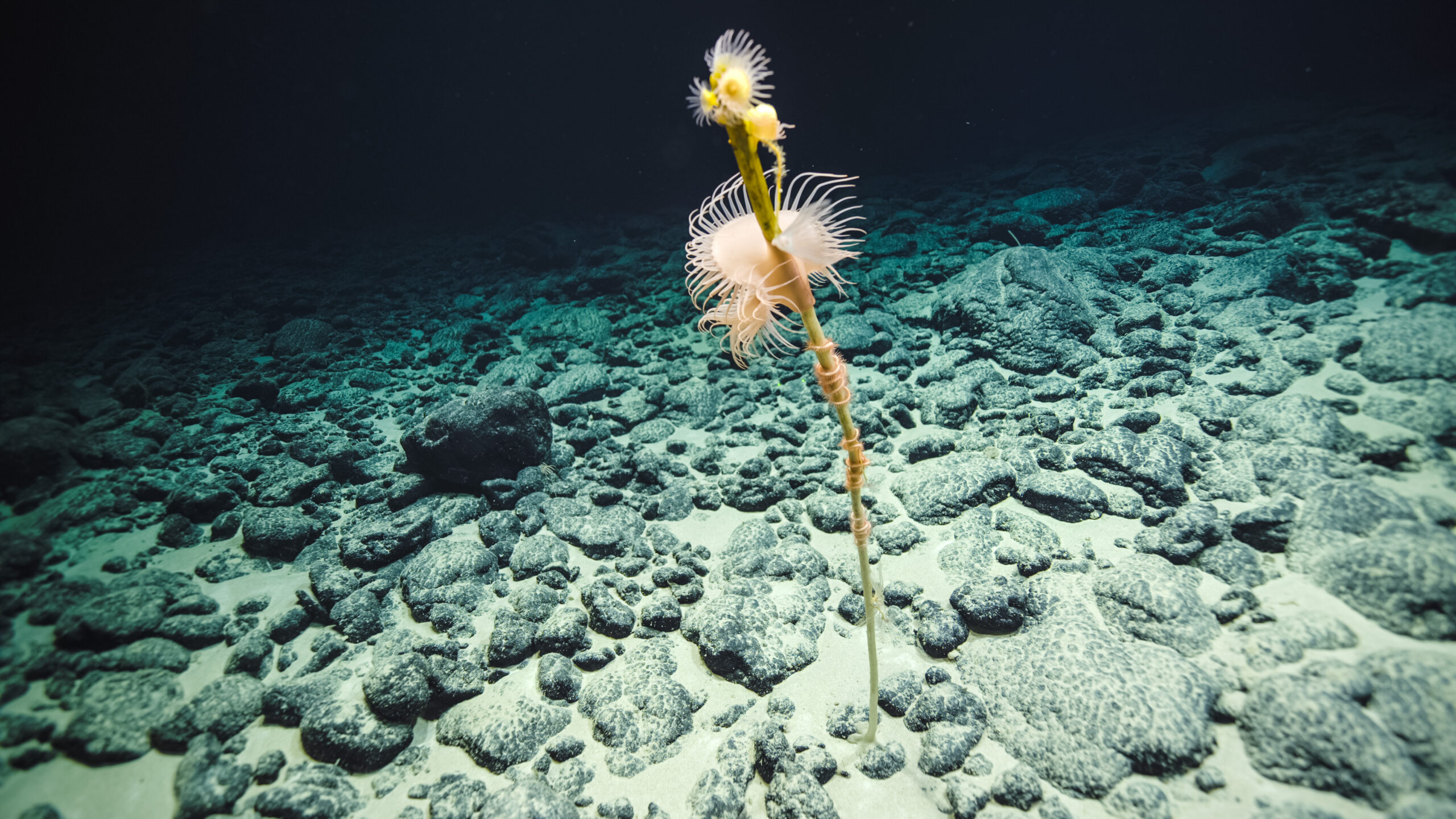

Crinoid and Octocoral

Discovered at a depth of 2,203m in the Jotul Hydrothermal Vent Field during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep (2024) expedition, this newly identified octocoral offers a rare glimpse into deep-sea commensalism.

With limited hard surfaces available in the deep ocean, the octocoral wraps around the stalk of a crinoid, using its structure for support without apparent harm to the host. This relationship is similar to forest epiphytes, such as ferns and mosses growing on trees, where one organism benefits from elevation and stability while the other remains largely unaffected.

“For better or for worse”

The brutal nature of parasitism

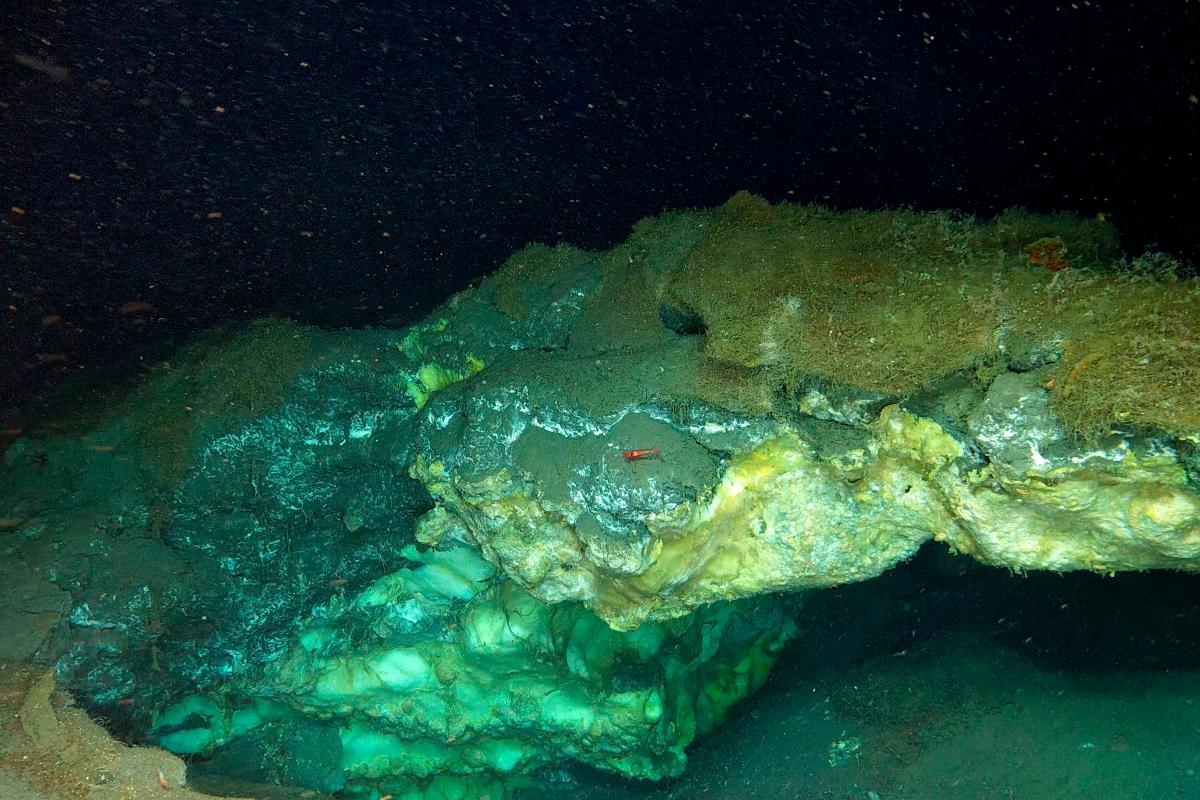

Rattail fish & parasitic copepods

During the Ocean Census South Sandwich Islands expedition, captured by the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s ROV SuBastian, we observed rattail fish (grenadiers) hosting parasitic copepods, highlighting an important but still poorly understood form of symbiosis: parasitism.

In this relationship, parasitic copepods attach to the fish’s skin, gills, or body cavities, where they feed on tissues, blood, or bodily fluids, benefiting at the expense of their host. The rattail fish may experience stress, tissue damage, or increased susceptibility to disease – leading to an earlier death of the individual host.

Octopus and leeches

On the same expedition, we also documented a striking example of parasitism involving octopuses and leeches.

In this interaction, marine leeches attach to the octopus’s skin or mantle, where they feed on blood or bodily fluids, gaining nourishment while harming the host. For the octopus, leech infestations can cause physical stress, tissue damage, and increased vulnerability to infection, and may also interfere with movement, camouflage, or normal behavior.

Interested in more ocean stories?

From cooperative partnerships to parasitic encounters, symbiosis shows that for some species, life in the deep ocean is a matter of interconnected relationships.

Follow Ocean Census on social media to stay inspired by new discoveries – and if you’re a scientist, join our Science Network for opportunities to get involved.

Related News

Join the census

The Ocean Census Alliance unites national and philanthropic marine institutes, museums, and universities, backed by governments, philanthropy, business and civil society partners.